Articles

La Chine a toussé et le monde s’est enrhumé. La réalisation de la métaphore prophétique à l’occasion de la pandémie du covid-19 nous ramène à une réalité désenchantée de la mondialisation et des chaînes de valeur globalisées qui organisent la conception, la production et la circulation des biens manufacturés. Durant les trente dernières années, la structuration des chaînes de valeur mondiales (CVM) a été guidée par la croyance que les progrès des technologies logistiques assureraient, de plus en plus efficacement, la maitrise des coûts, des délais et des risques des chaînes de valeur dispersées sur des espaces géographiques de plus en plus éloignés.

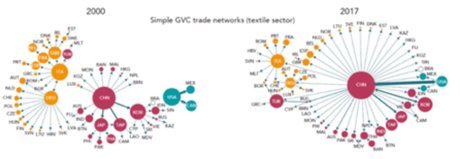

Si ce modèle de production a incontestablement permis, d'une part, de libérer le pouvoir d'achat des consommateurs par la réduction du coût d'acquisition de biens et services et, d'autre part, d'assurer l'émergence économique de certains pays en développement, il n'est pas exempt de critiques. En encouragent le développement de CVM, les politiques publiques et les stratégies industrielles de nombreux pays ont orchestré leur dépendance dans des secteurs majeurs comme l'automobile, le textile, l'électronique ou, plus inquiétant, les industries pharmaceutiques et de la santé. Le Global Value Chain Development Report 2019 de l'OMC et la Banque Mondiale montre comment les chaînes de valeur se sont massivement structurées autour d'un acteur central : la Chine qui s'accapare plus de 15% du marché mondial des exportations.

La crise du Covid-19 a révélé la vulnérabilité d'une logistique mondialisée fondée sur le recours par les grandes puissances industrielles à des sous-traitants ou des filiales lointain.e.s et souvent concentré.e.s. Depuis le début de la crise sanitaire des ruptures d'approvisionnement y sont constatées dans de nombreux secteurs vitaux. Les industries à forte intensité de main-d'œuvre comme l'automobile, les composants électroniques, les biens de consommation et le textile sont particulièrement éprouvées. Dans l'industrie de la santé, la paralysie de la production chinoise couplée à l'explosion de la demande d'équipements médicaux et de protection ont mis à l'épreuve d'un choc exceptionnel les perceptions des fragilités et des risques des chaînes logistiques mondialisées.

Par-delà le caractère conjoncturel de la crise sanitaire du covid-19, force est de reconnaître que le modèle fondé sur la fragmentation des espaces de production montre des signes de vulnérabilité qui contribuent à l'essoufflement du commerce mondial amorcé en 2008.

Le modèle des chaînes de valeur étendues et interdépendantes porte des vulnérabilités structurelles de natures économique, politique et sociétale.

- La hausse des coûts salariaux en Asie n'est plus compensée par des gains de productivité. A contrario, l'automatisation et la robotisation des tâches réduisent les coûts de production dans les pays industrialisés ;

- Les coûts de transport et les coûts cachés (malfaçons et non-qualité, aléas de livraison, etc.) contribuent à accroitre les coûts de production ;

- La résurgence des protectionnismes en Europe et aux Etats-Unis qui décourage les délocalisations par des mesures fiscales, douanières et non-douanières ;

- Les dispositions légales de contrôle des fournisseurs - comme la loi Sapin 2 en France - accroissent les risques juridique et financier liés aux délocalisations et à la sous-traitance en cascade ;

- Enfin, les aspirations à de nouvelles formes de consommation plus personnalisées et d'un meilleur impact social et environnemental s'apprêtent de moins en moins au modèle de fabrication dans des ateliers lointains et difficilement contrôlables.

A quelle transformation des chaînes de valeur peut-on s'attendre ? Nous proposons trois scénarii.

Scénario 1 : Business as usual

Si de nombreux économistes et décideurs politiques fustigent les fragilités des CVM et la forte dépendance à l'égard de la Chine, ils sont aussi nombreux à considérer qu'une transformation radicale et rapide est difficilement envisageable. Le degré d'interdépendance des économies et les investissements massifs engagés par les entreprises pour structurer leurs chaînes logistiques mondiales accréditent le scénario d'une reprise sur les mêmes bases qu'avant la crise.

Scénario 2 : la relocalisation nationale

La prise de conscience de la perte de souveraineté sanitaire devrait conduire à une intervention plus forte des Etats. La « relocalisation défensive » s'organiserait pour sécuriser les approvisionnements des biens vitaux.

Il est toutefois peu probable que le mouvement de balancier conduise à une relocalisation intégrale des systèmes de production dans la mesure où les grands donneurs d'ordres buteront sur deux obstacles : les capacités de production nationales et l'impact sur les prix des biens manufacturés.

Scénario 3 : la relocalisation régionale

Le scénario d'une relocalisation régionale serait plus probable et rationnel. Cette hypothèse repose sur une réorganisation autour de chaînes de valeur dédiées à des marchés géographiques régionaux, dans lesquels les entreprises ré-agencent leurs systèmes de production et ceux de leurs fournisseurs partenaires. L'implantation sur un territoire particulier de tout ou partie d'une filière de production serait alors tributaire des conditions d'attractivité en matière de ressources humaines, matérielles et énergétiques disponibles.

Si ces chaînes de valeur plus resserrées permettent une meilleure réactivité d'approvisionnement, elles ne garantissent pas la résilience du système productif. Celles-ci seraient favorisées par « la redondance » (l'accès à des capacités de fabrication supplémentaires au risque de la surcapacité), « la diversité » (l'accès à plusieurs sources d'approvisionnement) et « la modularité » (l'aptitude à reconfigurer un système et à recombiner des ressources) des systèmes de production.

La relocalisation régionale : Une opportunité pour le Maroc ?

Une relocalisation régionale - dans un espace Euro-Méditerranée-Afrique en particulier - peut être une opportunité pour le Maroc, en termes d'accroissement et de diversification de la demande, d'intégration des filières de production et de développement de capacités d'innovation notamment dans les secteurs de l'énergie renouvelable et de l'industrie 4.0.

Dans les secteurs automobiles, textile et des composants électroniques par exemples, le Maroc pourrait profiter du rapatriement dans un espace Euro-méditerranéen d'une partie des productions actuellement réalisées en Asie. Ce mouvement pourrait d'ailleurs s'accompagner de flux d'IDE asiatiques désirant conserver leurs clients européens en s'implantant au Maroc.

En illustrant la dépendance de l'économie mondiale à la Chine, l'épidémie du covid-19 pourrait influer sur sa structuration à l'avenir. Si l'organisation des chaînes de valeur est l'affaire des stratégies industrielles des entreprises, la crise sanitaire montre qu'elle est également l'affaire des Etats qui doivent protéger leurs citoyens et renforcer la résilience de leurs économies.

Hafsa EL BEKRI est Enseignante-Chercheure en économie internationale- Euromed Business School-Université Euromed de Fès. Hicham SEBTI est Docteur en Management de l'Université Paris-Dauphine et Directeur de Euromed Business School-Université Euromed de Fès.